The Recognition of Shelter in Retrospect

When everything that matters seems to have passed, unknowingly, through the same gate

There is a strange kind of realization that doesn’t come from searching, but from tracing backwards.

You spend years following your own instincts, toward songs, films, voices, tones. You never thought they were connected. Why would they be? Until one day, you notice:

“Everything that stayed with me… came from the same place.”

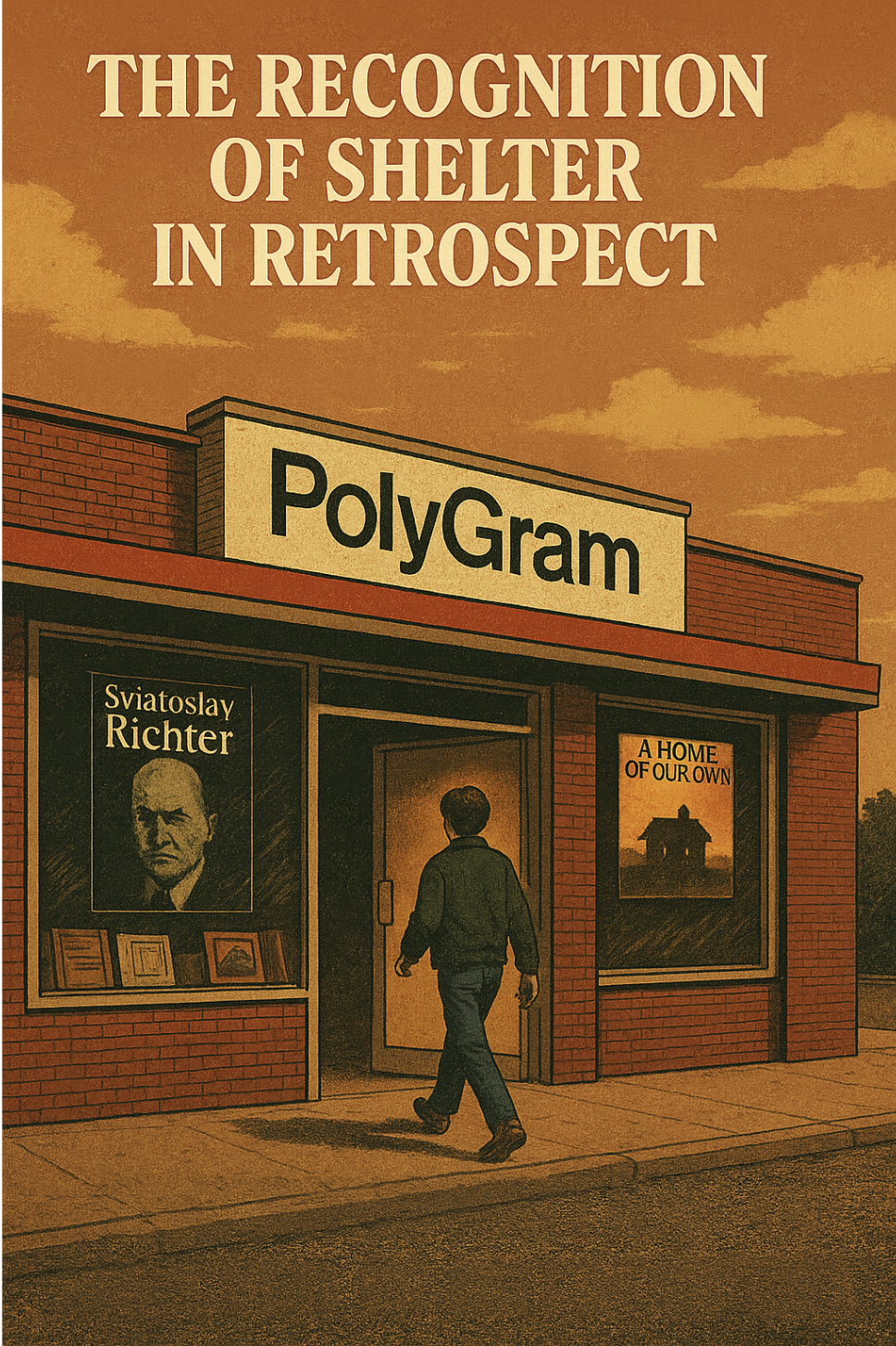

For me, that place was PolyGram.

This isn’t about loving a brand, or indulging in nostalgia.

It’s about standing at the far edge of my own emotional landscape and realizing that the voices that had shaped and continued to mold me, things like Angus Tung’s philosophical warmth, Steve Chow’s gentle restraint, Sviatoslav Richter’s sovereign sadness, even A Home of Our Own’s quiet dignity - they all passed, unknowingly, through the same gate.

They weren’t curated for me. PolyGram never knew I existed.

But for a brief moment in time, this vast and unwieldy corporate structure became a kind of shelter. A space where sincerity was allowed a space. Where emotional depth wasn’t filtered out in the name of efficiency or market trends.

Someone, somewhere in the machinery seemed to have believed: “This is worth protecting. Someone out there will care. Maybe not today, maybe not loudly. But one day, they’ll be listening.”

And they are.

The Unseen Hands

It’s tempting to imagine this as a grand design, a perfect curation by wise executives. But the truth is quieter, and more fragile.

It happens because of a few rare individuals, scattered across production teams, mastering rooms, and A&R offices, who carry a sense of responsibility that no job description requires. They aren’t saints or strategists. But for reasons often mysterious even to themselves, they hold the line.

They protect coherence. They safeguard a kind of aesthetic and moral integrity against the constant pressures of metrics and profit.

It’s not easy. It never was. To act with integrity inside a machine built for expedience often means working against your own interest. But these people, in big ways and small, simply couldn’t not do it.

It’s what Viktor Frankl meant when he wrote: “What is to give light must endure burning.”

Even as a large, capitalist entity like PolyGram, somewhere, quietly, there were people like that, who thought:

“I can’t kill this. I don’t know who it’s for, but I know it’s true.”

And they didn’t. Which is why, years later, people like me who found it, felt:

“Everything I love, found a home here.”

That’s why PolyGram felt different. It wasn’t a corporate masterstroke. It was the accidental alignment of these individuals’ quiet acts of refusal, forming brief pockets of resistance where real things survived.

A Philosophy of Sound

PolyGram itself was never meant to be a shelter. Formed in 1972 from a merger of the Dutch company Philips’ record division and Germany’s Siemens’ Deutsche Grammophon, PolyGram grew into one of the world’s largest music companies through the 70s, 80s, and 90s.

It spanned continents and genres: from classical powerhouses like Deutsche Grammophon and Philips, to pop labels like Mercury, Motown and Island Records, to Asian subsidiaries releasing Mandarin ballads that would shape a generation.

Unlike most, PolyGram wasn’t originally built to manufacture trends. It was built to preserve sound and beauty, then accidentally inherited pop, soul, and film.

In the late 70s–90s, its classical divisions DG, Decca, Philips invested in recordings that would not be profitable for decades. Some only became revered in the 2000s and 2010s.

Even in pop and film, they picked people and projects that didn’t test well, didn’t fit categories, didn’t scream “hit”, but had something durable.

Their foundations were engineers, archivists, cultural caretakers. They were able to say:

“Let’s record this, because it matters. Even if it sells slowly.”

You can feel that in every artist of theirs you love.

In 1998, PolyGram was absorbed into Universal Music Group. The shelter dissolved. The industry consolidated. But for a few decades, something improbable had existed. And they will continue to exist with its catalogs.

To the Someone, Somewhere

I realize now that what moved me about PolyGram wasn’t perfection. It wasn’t that every work they touched was great. They weren’t.

But as long as it lasted, they gave people room to create sincerely, without immediate commercial justification. Songs were written not to chase trends but to capture something true. Films were made not for algorithms but for resonance.

I think about that a lot as I write this. I know this piece isn’t optimized. It isn’t designed for mass appeal or search engines or social algorithms.

I’m writing for resonant souls who are too serious for commercial cynicism but too moving to be obscure. Someone, somewhere, someday who will care. Someone sitting alone at night, tracing back through their favorite voices, trying to find coherence in a fragmented world.

If you’re reading this and it lands, know this: The world once made room for what you value most. And maybe, in small ways, it still can.

For the Curious

Have you ever noticed this in your life?

That the voices, melodies, films, or works that mattered most, the ones that lasted, all came from the same unnamed place?

What was your shelter in retrospect?